What Is Bell’s Palsy?

Bell’s palsy is a sudden, temporary weakness or paralysis of the muscles on one side of the face, caused by inflammation of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). It happens without warning-often waking someone up with a drooping eyelid, slurred speech, or difficulty smiling. Unlike a stroke, Bell’s palsy doesn’t affect the brain; it’s a problem with the nerve itself, swollen and compressed inside a narrow bony tunnel called the fallopian canal. About 15 to 30 people out of every 100,000 get it each year, mostly between ages 15 and 45. It’s not contagious, not caused by stress, and not a sign of a brain tumor. After ruling out other causes like infection or trauma, doctors diagnose it as idiopathic-meaning no clear reason is found.

Why Corticosteroids Are the Gold Standard Treatment

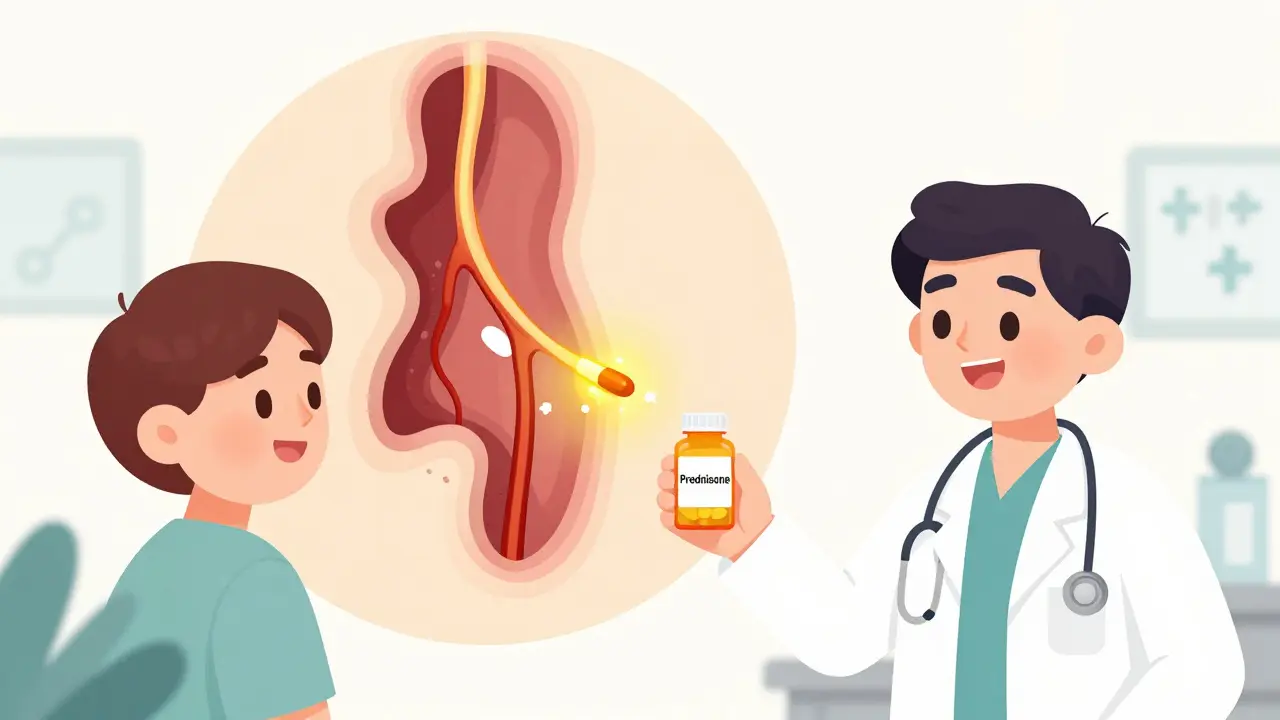

For decades, doctors watched and waited, hoping the face would recover on its own. About 70% of people did, but many were left with lingering weakness, facial tightness, or involuntary movements called synkinesis. Then came the evidence: corticosteroids are the most effective treatment. High-quality studies, including a 2019 Cochrane review of 895 patients across seven trials, show that corticosteroids cut the chance of incomplete recovery by about 31%. The number needed to treat (NNT) is just 10-meaning if you treat 10 people, one will avoid lasting damage.

The mechanism is simple but powerful. When the facial nerve swells inside its tight bony canal, it gets pinched. Corticosteroids like prednisone reduce that swelling, taking pressure off the nerve so it can heal properly. Without this, the nerve may not recover fully, even if it eventually regenerates.

The Right Dose and Timing Matter

Not all corticosteroid use is the same. The standard, evidence-backed regimen is oral prednisone at 50 to 60 mg daily for five days, followed by a five-day taper down to zero. That’s a total of 500 mg over 10 days. Doses under 450 mg total are linked to much higher rates of poor recovery-up to 30%-while doses of 450 mg or more bring recovery rates down to 14%.

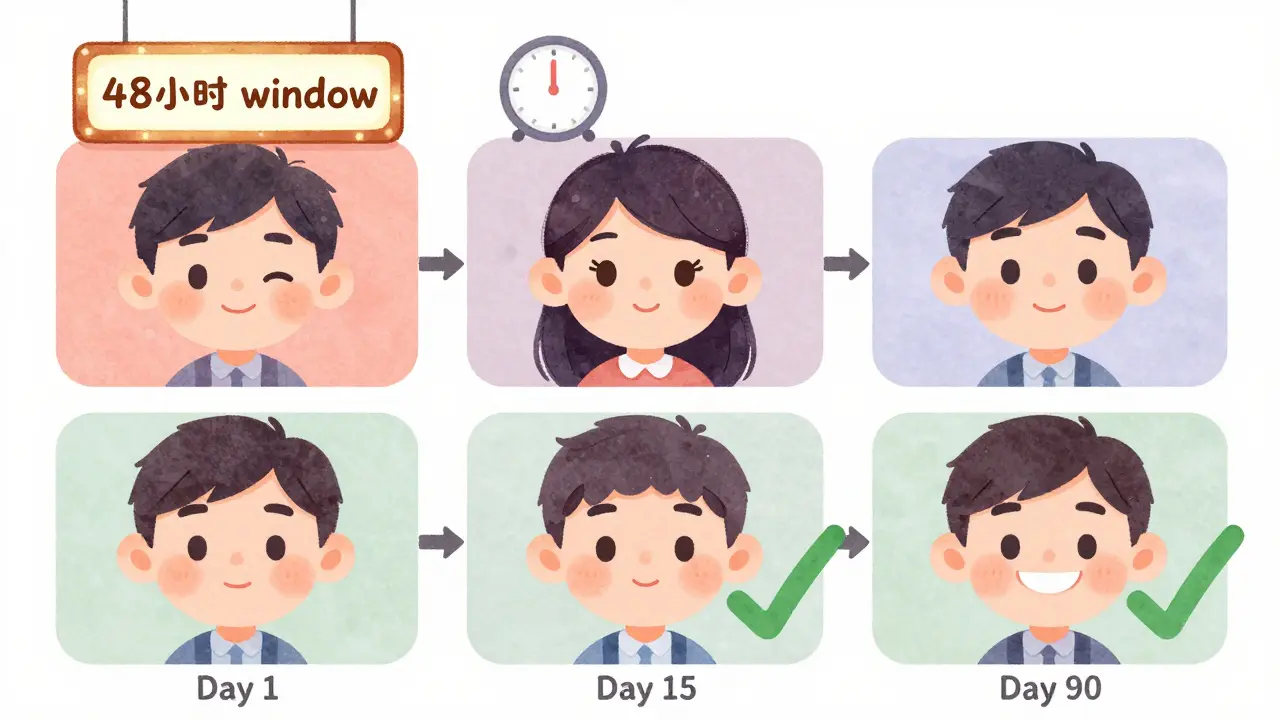

Timing is even more critical. Treatment must start within 48 hours of symptoms appearing. After 72 hours, the benefit drops sharply. A 2023 machine learning study of 493 patients found that the single biggest factor influencing recovery, after age, was whether corticosteroids were started early. Patients who waited five days reported significantly slower and less complete recovery compared to those who started within 24 hours.

Corticosteroids vs. Antivirals: What Actually Works

Many patients hear about antivirals like acyclovir or valacyclovir being used for Bell’s palsy. That’s because some believe the virus herpes simplex might trigger it. But here’s the truth: antivirals alone do nothing. The AAFP’s 2023 review found no high-quality evidence supporting antiviral monotherapy. Taking antivirals by themselves won’t improve your chances of full recovery.

Combining antivirals with corticosteroids is a different story. There’s moderate-quality evidence that this combo may reduce the risk of synkinesis-the awkward muscle spasms that happen when nerves misfire during healing. The relative risk drops by about 33%. But it doesn’t make you recover faster or more completely. That’s why major guidelines say combination therapy can be considered, especially if symptoms are severe, but corticosteroids alone are still the baseline.

What About Other Treatments?

There’s a lot of noise out there: laser therapy, hyperbaric oxygen, steroid injections into the ear, stellate ganglion blocks. Some clinics offer them. Some patients swear by them. But the data doesn’t back them up. A 2023 review from the American Academy of Family Physicians looked at 32 to 35 studies on these alternatives-and found zero high-quality evidence they work better than corticosteroids. None are recommended as first-line treatments. If you’re considering one, ask: Is there a randomized trial showing it outperforms prednisone? If not, stick with what’s proven.

Side Effects: What to Expect

People hear "steroids" and think of weight gain, diabetes, or mood swings. Those are real risks-but only with long-term use. For Bell’s palsy, you’re on the medication for 10 days. That’s not enough time for serious side effects to develop.

In clinical trials involving 715 patients, there was no significant difference in side effects between those taking prednisone and those taking a placebo. The most common complaints were temporary: trouble sleeping, increased appetite, and mild mood changes. One study noted three people had sleep disturbances. Diabetic patients need to monitor blood sugar closely during treatment, as prednisone can cause short-term spikes. But for most people, the side effects are mild and fade as soon as the course ends.

What Happens If You Delay Treatment?

Many patients don’t realize they have Bell’s palsy right away. They think it’s a toothache, a sinus infection, or even a stroke. The average time from symptom onset to seeing a doctor is 3.2 days. That’s already past the ideal window.

Delays lead to worse outcomes. In one UK study, patients who got treatment after 72 hours were twice as likely to have lasting facial weakness. Misdiagnosis happens in 15-20% of cases. That’s why it’s crucial to know the signs: sudden one-sided facial droop, inability to close the eye, loss of taste on the front of the tongue, or pain behind the ear. If you see these, don’t wait. Go to urgent care or your GP immediately. Early treatment isn’t just helpful-it’s essential.

Recovery: What to Expect Over Time

Recovery isn’t instant. Most people start seeing improvement within two to three weeks. By three months, 72.6% of treated patients recover fully. By nine months, that number jumps to 89.5%. The House-Brackmann scale is used to measure progress-from Grade I (normal) to Grade VI (complete paralysis). Doctors use this to track improvement and decide if further intervention is needed.

Some people don’t recover completely. About 10-15% have mild residual weakness. A smaller group develops synkinesis, where smiling causes the eye to twitch. Physical therapy and Botox can help with these issues, but prevention through early corticosteroid use is far better than managing complications later.

How Clinicians Confirm the Diagnosis

Doctors don’t just guess. They rule out other causes. A stroke can mimic Bell’s palsy, but it usually affects more than just the face-like arm weakness or speech trouble. Ramsay Hunt syndrome, caused by the shingles virus, causes a painful rash around the ear and may need antivirals. Tumors or trauma can also cause facial paralysis. If symptoms don’t improve after corticosteroids, or if there are other neurological signs, imaging like an MRI may be ordered.

Most clinics now use the House-Brackmann grading system to document severity at diagnosis and track progress. Over 90% of neurology practices in the UK use it. It’s simple, reliable, and helps patients understand their recovery path.

What’s Changing in Treatment Today?

There’s no new miracle drug coming soon. Corticosteroids remain the gold standard because they work, are cheap (a 10-day course of generic prednisone costs under $5 in the U.S.), and have a strong safety profile. But research is moving toward personalization.

Machine learning models now predict recovery chances based on age and treatment timing. Children under 12 still lack strong data, so dosing is adjusted carefully. Future studies are looking at biomarkers-blood tests that might show who will respond best to steroids. For now, the message is clear: if you have sudden facial weakness, act fast. Get corticosteroids within 48 hours. That’s the single most important thing you can do.

Final Takeaway

Bell’s palsy is scary, but treatable. It’s not a stroke. It’s not permanent. And it’s not something you have to suffer through. The evidence is overwhelming: corticosteroids, taken early and at the right dose, give you the best shot at a full recovery. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’ll get better on its own. Don’t get distracted by unproven treatments. If your face drops suddenly, see a doctor within two days. Your face will thank you.

Cheryl Griffith

I had Bell’s palsy last winter-woke up like I’d been punched in the face. Went to urgent care, got prednisone same day, and honestly? My eye stopped drooping in 48 hours. I didn’t believe it until I saw myself in the mirror. Don’t wait. Just go.

Also, please stop scrolling and actually listen to your doctor. This isn’t a myth. It’s science.

My dog even noticed I was smiling again. He cried. (Okay, he didn’t. But I swear he looked proud.)

January 16, 2026 AT 22:11

Stephen Tulloch

LMAO at all the people who think ‘natural remedies’ work for this 😂

You want to ‘balance your chi’? Cool. Meanwhile, your facial nerve is getting crushed in a bony tomb and you’re lighting sage. Go take the damn prednisone, Karen. It’s $5. It’s FDA-approved. It’s not magic, it’s medicine.

Also, if you’re reading this and still waiting for ‘vibrational healing’-just know your synkinesis will be *artistic*.

-Stephen, MD dropout who still knows more than your TikTok guru

January 17, 2026 AT 06:26

Henry Ip

My cousin had this last year. She waited 5 days because she thought it was a bad toothache. Ended up with synkinesis-smiles make her eye blink like a broken strobe. She does Botox now. Costs a fortune. Took her 8 months to get back to normal.

Don’t be her. Get the steroids. Fast.

And yeah, antivirals? Waste of time unless you’ve got a rash. Don’t let your doctor push them unless they’re adding steroids too.

January 18, 2026 AT 07:06

Nicholas Gabriel

Let’s be clear: Bell’s palsy isn’t ‘stress-related,’ and no, your ‘energy healer’ isn’t helping. The facial nerve is swollen-period. Corticosteroids reduce swelling. That’s it. No mysticism. No crystals. No ‘chakra alignment.’

And if you’re reading this and thinking, ‘I’ll just wait and see,’ please, for the love of all that is medically sound, go to a clinic NOW.

The 48-hour window isn’t a suggestion-it’s a biological deadline. Miss it, and you’re gambling with your smile. That’s not dramatic. That’s data.

Also, the House-Brackmann scale? It’s the only thing that matters. Ask for it. Demand it. Write it down. Track it.

And for the love of God, stop Googling ‘Bell’s palsy alternative cures.’ You’re not saving money. You’re wasting time.

-Nicholas, who’s seen too many patients with permanent asymmetry because they trusted YouTube

January 19, 2026 AT 01:44

Corey Sawchuk

My uncle had this back in the 90s. He didn’t get steroids because his doctor said ‘it’ll pass.’ Took him two years to get back to 80%. He still can’t whistle.

Anyway, I showed this to my mom. She’s 72. She said ‘I’m going to print this out and stick it on the fridge.’

Just saying. Sometimes the simplest thing works best.

Also, prednisone made me hungry. A lot. Ate three bags of chips. No regrets.

January 20, 2026 AT 08:43

evelyn wellding

OMG I JUST HAD THIS!! 😱 I woke up and couldn’t close my eye and thought I was having a stroke!! Ran to the clinic and they gave me prednisone same day!! I’m already feeling better in 3 days!! 🙌

Y’all need to know this!! Don’t panic!! But DO act!!

Also I got a cute eye patch from Target and it made me feel like a pirate 😎❤️

January 20, 2026 AT 11:50

Ryan Hutchison

Why are we even talking about this? In America, we’ve got the best medicine in the world. If you’re waiting for some ‘natural cure’ or ‘Ayurvedic magic’ you’re not just being foolish-you’re being un-American.

Prednisone is cheap, proven, and made right here. No other country has this kind of access. If you’re in India or Canada and you’re not getting this treatment, that’s a failure of your system.

Stop letting global nonsense dilute American science.

-Ryan, born and raised in Ohio, and proud of it

January 20, 2026 AT 17:25

Rob Deneke

Had this last year. Took steroids on day 2. Started improving in 3 days. Full recovery in 6 weeks.

Best advice? Don’t stress. Don’t stare in the mirror all day. Just take the pills, sleep, and trust the process.

Also-your face doesn’t need to be ‘fixed.’ It’s healing. Let it.

And yes, you can still kiss someone with a crooked smile. They’ll love you anyway.

January 20, 2026 AT 20:59

Samyak Shertok

What if Bell’s palsy isn’t a disease… but a message?

What if your face is trying to tell you: ‘You’re smiling too much for the wrong reasons?’

What if the nerve isn’t swollen… but silenced?

What if prednisone doesn’t heal you… but numbs you to the truth?

I’ve seen people recover. But I’ve also seen people become… hollow. Like their smiles became performances.

Maybe the real cure isn’t in the pill.

Maybe it’s in the silence after the diagnosis.

-Samyak, who meditated for 14 days while his friend took steroids and recovered faster

January 20, 2026 AT 23:15

Riya Katyal

Oh wow, so you’re telling me the only thing that works is a cheap steroid pill? And I thought I’d need a $5000 laser machine and a 12-step spiritual program?

Wow. What a relief. I was gonna sell my kidney for a ‘facial frequency wand’ on Etsy.

Thanks for saving me $4,000 and my dignity.

Also, I’m still mad my cousin told me to ‘cry it out’ and ‘visualize my cheek lifting.’

She’s now my ex-cousin.

January 22, 2026 AT 07:45

Nicholas Gabriel

Just saw someone reply saying ‘it’s a spiritual message.’

Look. If your face drops, and you’re not in a horror movie, it’s not a metaphor. It’s a swollen nerve.

Go take the pill. Don’t overthink it.

And if you’re still here reading this instead of calling your doctor? You’re already late.

-Nicholas, who still can’t believe people believe in ‘energy healing’ for Bell’s palsy

January 24, 2026 AT 02:53