When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 bottle of generic lisinopril, it’s easy to think you’re getting a bargain. But here’s the twist: you are getting a bargain-compared to almost every other developed country. At the same time, if you’re paying $500 for a brand-name drug like Jardiance, you’re paying nearly four times what someone in Japan or Australia pays for the same pill. The U.S. doesn’t have high drug prices across the board. It has two drug markets: one where generics are dirt cheap, and one where brand-name drugs are the most expensive in the world.

Generic Drugs in the U.S. Are Cheaper Than Almost Everywhere Else

Here’s a fact most people don’t know: 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. And those generics? They cost, on average, 33% less than the same drugs in countries like Canada, Germany, or the U.K. According to a 2022 study by the RAND Corporation, the U.S. pays just 67 cents for every dollar spent on generics elsewhere. That’s not a fluke. It’s the result of a market built on fierce competition.

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, dozens of companies rush to make copies. The FDA approves them quickly. Once three or four manufacturers enter the market, prices drop to 15-20% of the original brand price. That’s not theory-it’s data. IQVIA’s sales reports show that when five companies sell the same generic, prices often fall below $5 for a 30-day supply. In many cases, you can buy generic metformin for $4 at Walmart. In the U.K., the same amount costs $12. In France, it’s $15.

Why does this happen? Volume. The U.S. buys more generic drugs than any other country. That gives pharmacies and insurers massive negotiating power. Medicare Part D, which covers millions of seniors, buys generics in bulk and demands deep discounts. Even private insurers use their size to squeeze prices down. The result? A system that works-when it’s not broken by monopolies.

Brand-Name Drugs? The U.S. Is the Most Expensive Market on Earth

But flip the script, and everything changes. For brand-name drugs-those still under patent-the U.S. is the outlier. The same RAND study found U.S. list prices for originator drugs are 422% higher than in other OECD countries. That means if a drug costs $100 in Japan, you’ll pay $422 in the U.S. before insurance.

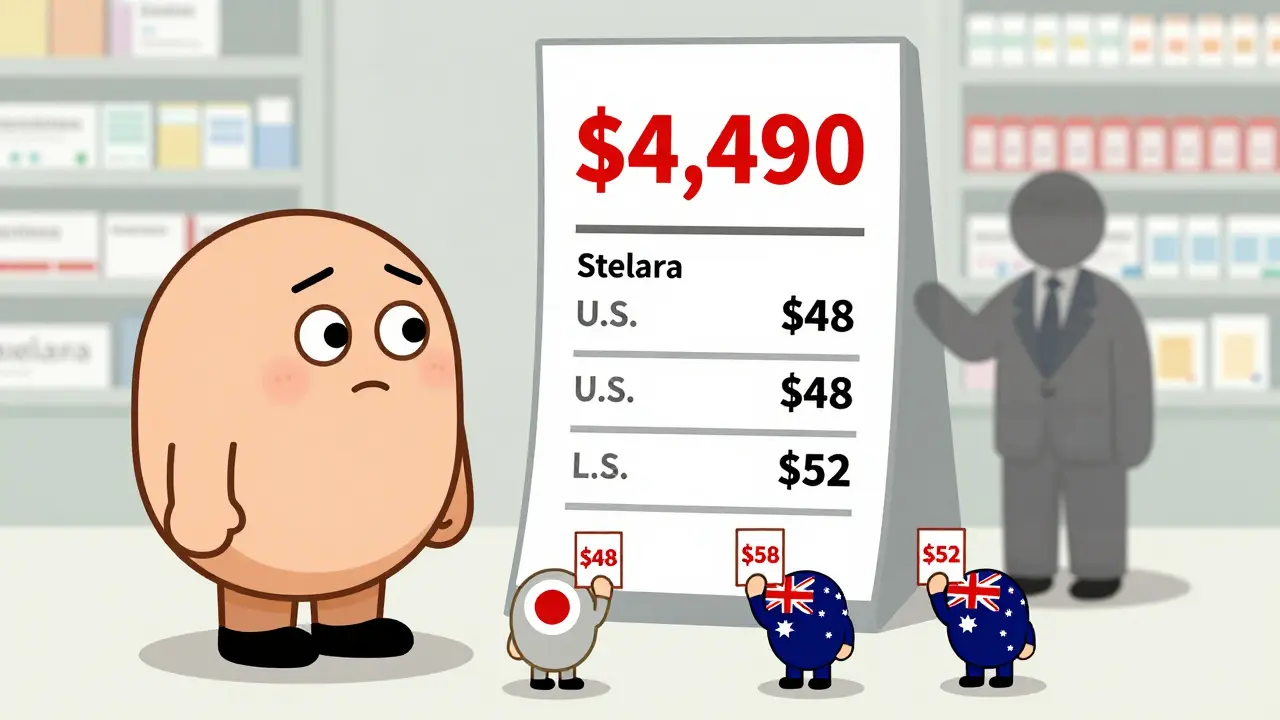

Take Jardiance, a diabetes drug. In Australia, it costs about $52 per month. In Japan, it’s $48. In the U.S., Medicare negotiated a price of $204. That’s not a discount-it’s still nearly four times the global average. Stelara, used for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, costs $2,822 in the U.K. In the U.S., Medicare pays $4,490. Even after negotiations, the U.S. still pays more.

Why? Because the U.S. doesn’t negotiate prices the way other countries do. In Canada, Germany, and France, the government sets a maximum price based on what it thinks the drug is worth. In the U.S., drugmakers set the price-and then insurers, PBMs, and Medicare try to claw it back with rebates. That’s why list prices look insane, but net prices (after rebates) are lower.

The Rebate Trap: Why List Prices Lie

Here’s where things get confusing. You see a drug listed at $1,000 on a pharmacy’s website. But you pay $50. Why? Because the manufacturer gave a rebate to your insurer. That rebate doesn’t go to you-it goes to the middlemen. The system is designed so that insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) get paid based on how much they negotiate down the list price. The higher the list price, the bigger the rebate-and the bigger the cut for the middleman.

That’s why drugmakers raise list prices every year, even when the actual cost to make the drug hasn’t changed. It’s not about profit-it’s about the rebate game. A 2024 University of Chicago study found that when you look at net prices after rebates, the U.S. actually pays 18% less than countries like Canada and Germany for the same drugs. But here’s the catch: those rebates don’t help patients who pay out-of-pocket. If you don’t have insurance, you pay the full list price. And that’s where the U.S. becomes unaffordable.

Why Some Generics Suddenly Become Expensive

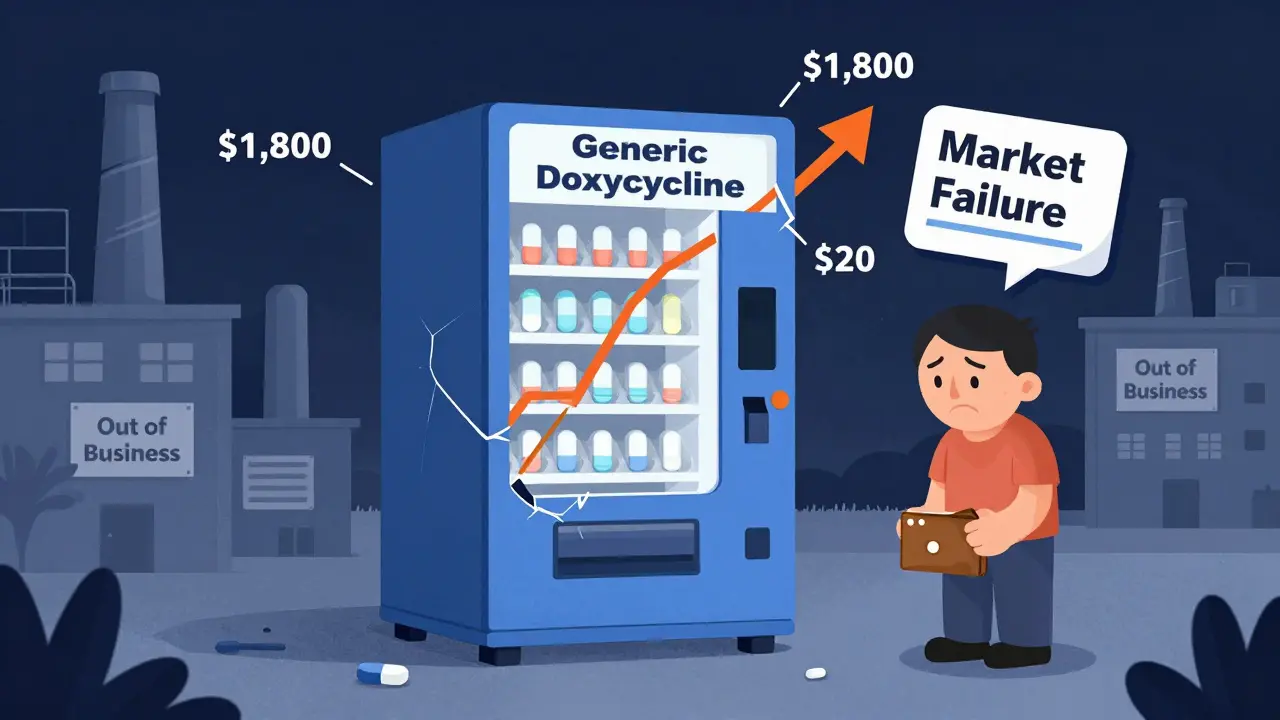

It’s not always cheap. Sometimes, a generic drug that’s been on the market for years suddenly spikes in price. Why? Because the competition disappeared.

When a generic drug has only one or two makers, prices stay low. But if one company goes bankrupt, gets bought out, or decides to quit making the drug, the market can collapse. That’s what happened with doxycycline, a common antibiotic. In 2013, dozens of companies made it. By 2018, only two were left. Prices jumped from $20 for a 30-day supply to $1,800. The FDA documented over 200 cases of generic drug shortages since 2010, many caused by manufacturers leaving the market because profits were too thin.

It’s a cruel irony: the system that keeps generics cheap also makes it risky for manufacturers to stay in. If the price drops too low, they lose money. So they exit. Then the few remaining companies raise prices. The FDA calls this “market failure.” Patients call it price gouging.

Medicare’s Negotiations: A Step Forward, But Not Enough

In 2022, Congress gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs. The first round of negotiations lowered prices for drugs like Jardiance and Eliquis-but not enough. Medicare’s negotiated price for Jardiance is still 3.9 times higher than the average price in 11 other countries. For Stelara, it’s 1.6 times higher. And these are the drugs Medicare picked because they were the most expensive.

So what’s the point? It’s a start. But the real savings come from generics. The FDA estimates that the 773 generic drugs approved in 2023 will save the U.S. system $13.5 billion in a single year. That’s more than all the Medicare negotiations combined. Accelerating generic approvals is the most powerful tool we have to bring down drug costs.

What This Means for You

If you’re on a generic drug, you’re winning. You’re paying less than people in most other countries. Keep using mail-order pharmacies, shop around with GoodRx, and ask your doctor if there’s a generic alternative. Most of the time, there is.

If you’re on a brand-name drug, you’re paying the price for a broken system. Ask your doctor about biosimilars-these are cheaper versions of biologic drugs that work just like the original. Check if your drug is on Medicare’s negotiation list. If it’s not, call your insurer and demand they negotiate. And if you’re paying cash, always ask for the cash price. Sometimes it’s lower than your insurance copay.

The U.S. doesn’t have a drug pricing problem. It has two. One is solved: generics are cheap because competition works. The other is still broken: brand-name drugs are priced like luxury goods because no one’s forcing the makers to lower them. Until that changes, Americans will keep paying more for the same pills-and the rest of the world will keep paying less.

How to Save on Medications Right Now

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare: These apps show you the lowest cash price at pharmacies near you, often lower than insurance copays.

- Ask for a 90-day supply: Many generics cost less per pill when bought in bulk.

- Check for manufacturer coupons: Even brand-name drugs often have discount cards that cut the price in half.

- Switch to generic: If your doctor prescribes a brand-name drug, ask: “Is there a generic version?” In 90% of cases, there is.

- Use mail-order pharmacies: For chronic meds, mail-order often cuts costs by 30-50%.

Why are U.S. generic drug prices lower than in other countries?

U.S. generic drug prices are lower because of massive market competition. Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, dozens of manufacturers rush to produce copies. With 90% of U.S. prescriptions being generics, pharmacies and insurers buy in huge volumes and demand deep discounts. The FDA also approves generics quickly, keeping the market flooded with low-cost options. In contrast, countries like France and Japan limit the number of generic manufacturers allowed to sell, which reduces competition and keeps prices higher.

Are brand-name drugs really that much more expensive in the U.S.?

Yes. For originator brand-name drugs, the U.S. pays 422% more on average than other OECD countries. For example, Jardiance costs $52 in Australia and $48 in Japan, but Medicare’s negotiated price in the U.S. is $204. Even after rebates, U.S. list prices remain far higher because drugmakers set them without government price controls. Other countries negotiate or cap prices; the U.S. doesn’t-until recently with Medicare’s limited negotiation program.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become expensive?

Generic drug prices spike when competition disappears. If only one or two companies make a drug, they can raise prices without fear of losing customers. This often happens when manufacturers exit the market due to low profit margins. The FDA has documented over 200 cases since 2010 where a shortage of generic manufacturers led to price spikes of over 1,000%. Doxycycline, for example, jumped from $20 to $1,800 per bottle after most makers left the market.

Does Medicare negotiation lower drug prices enough?

Medicare’s negotiation has lowered prices for 10 high-cost drugs, but not to global levels. In all but one case, the countries studied (Australia, Japan, Germany, etc.) still have lower prices than Medicare’s negotiated rate. For example, Stelara costs $2,822 in the U.K. but $4,490 under Medicare’s deal. The real savings come from generics, not negotiations. The FDA estimates that 773 new generic approvals in 2023 will save $13.5 billion-far more than Medicare’s negotiated savings.

What’s the difference between list price and net price?

List price is what the drugmaker charges before any discounts. Net price is what the insurer or government actually pays after rebates and discounts. In the U.S., list prices are inflated to create bigger rebates for pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), who get paid based on the discount amount. This makes the list price look outrageous, but net prices are often lower than in countries without rebates. However, patients without insurance still pay the full list price, which is why many struggle to afford drugs.

Can I buy cheaper drugs from other countries?

Technically, importing drugs from Canada or other countries is illegal under U.S. law, though enforcement is rare. Some people order from Canadian pharmacies and receive their meds without issue. The FDA allows limited personal importation under specific conditions, but it’s risky and not guaranteed. The safer, legal way is to use U.S.-based discount programs like GoodRx, which often match or beat international prices without breaking any rules.

What’s Next for Drug Pricing?

The next round of Medicare-negotiated drugs is due by February 1, 2026. That could mean 15-20 more drugs get price caps. But the real game-changer will be if the U.S. starts pushing for international price alignment-either by linking Medicare prices to global averages or by forcing drugmakers to offer the same price overseas as they do here.

Some experts argue that U.S. high prices fund global innovation. Others say it’s unfair to make Americans pay for the world’s R&D while other nations free-ride. The truth? The system is unsustainable. Either the U.S. will force down brand-name prices, or other countries will stop buying U.S.-made drugs. Either way, change is coming.

For now, know this: if you’re on a generic, you’re getting one of the best deals in global healthcare. If you’re on a brand, you’re paying the cost of a system that hasn’t caught up with reality. The fix isn’t complicated-it’s competition. More generics. More transparency. Less rebate games. And for the first time, a government willing to say: no more.

Antwonette Robinson

Wow, so the U.S. is basically the only country where you can get a 30-day supply of metformin for $4... and then get billed $200 for a brand-name drug that’s literally the same chemical. Genius. 🤡

February 3, 2026 AT 20:45

caroline hernandez

Let’s unpack this systemic bifurcation: the generic market operates under perfect competition dynamics with economies of scale, while the branded segment is a rent-seeking oligopoly protected by patent evergreening and PBM rebate structures. The real policy failure isn’t pricing-it’s structural misalignment between payer incentives and patient outcomes.

February 5, 2026 AT 19:49

Sherman Lee

They don’t want you to know this… but the FDA? Controlled by Big Pharma. The ‘competition’ in generics? A rigged game. One company makes it, then gets bought by the same conglomerate that makes the brand. Prices drop… then boom, ‘supply chain issue’ and it’s $1,800. 🤫👁️🗨️

They’re playing 4D chess with our prescriptions. You think this is about health? Nah. It’s about control.

February 6, 2026 AT 23:23

Coy Huffman

kinda wild how we’ve built this system where the cheapest meds are the ones everyone needs… and the expensive ones are the ones that save lives. it’s like we reward suffering with cash and punish survival with coupons.

maybe the real problem isn’t the price-it’s that we’ve made medicine a game of who can afford to play.

and honestly? i’m tired of being the guy who has to choose between insulin and rent.

we’re not broken. we’re just… not trying.

February 8, 2026 AT 18:23

Kunal Kaushik

Man, this hits different when you’re from India and your mom gets her blood pressure meds for $0.50 a pill here. I remember when she had to travel 300km just to get generics. Now she orders them online for less than a cup of chai. The U.S. system is wild. 🤯

February 8, 2026 AT 21:45

Mandy Vodak-Marotta

Okay but let’s be real-how many of us actually know that the $4 metformin at Walmart is cheaper than in Canada? I didn’t. I thought we were all getting screwed equally. Turns out, we’re getting screwed in two different ways. One way? We win. The other way? We’re literally crying in the pharmacy aisle while the cashier says ‘That’ll be $204.’

And don’t even get me started on the rebate trap. It’s like the pharmacy is running a scam where the middleman gets paid more the more you pay. So the higher the price, the more money someone else makes. That’s not capitalism. That’s a fever dream written by a Wall Street intern on Adderall.

Also, GoodRx saved my life last year. I was paying $120 for my thyroid med. Found it for $18. I cried. I’m not even ashamed.

February 10, 2026 AT 17:31

Harriot Rockey

Hey, if you’re on a generic-you’re winning. Seriously. 🙌

Don’t let anyone make you feel bad for using GoodRx or switching to a 90-day supply. That’s not gaming the system-that’s being smart. And if you’re on a brand-name drug? You’re not alone. Ask your doc about biosimilars. They’re legit. They’re cheaper. They work.

And if your insurer won’t budge? Call them. Again. And again. And then call again. We’ve got to make noise. No one’s coming to save us. But we can save each other.

Also-emoji for solidarity: 💊❤️

February 11, 2026 AT 07:24

Demetria Morris

People who use GoodRx are just enabling the system. You think you’re saving money? You’re just propping up a broken, greedy industry that’s designed to make you feel like you’re getting a deal while they laugh all the way to the bank. If you really cared, you’d demand systemic change-not cheap hacks. You’re not a savvy shopper. You’re a pawn.

February 11, 2026 AT 22:34

Geri Rogers

Okay, Demetria, you’re wrong. And I’m not sorry. 😤

Using GoodRx isn’t enabling the system-it’s surviving it. People can’t wait for ‘systemic change’ when they’re choosing between insulin and groceries. We don’t have the luxury of purity. We need tools NOW.

And guess what? The FDA approved 773 generics last year-that’s $13.5 BILLION in savings. That’s not a hack. That’s a revolution.

So stop preaching. Start helping. And if you don’t know how? Here’s a tip: stop judging people who are trying to stay alive.

February 13, 2026 AT 19:57

Samuel Bradway

my aunt just got on Medicare’s negotiation list last month. her stelara went from $4k to $2.8k. still crazy high… but at least she can breathe now.

we’re not fixing it all at once. but we’re fixing it a little at a time.

and honestly? that’s more than i thought we’d get.

February 13, 2026 AT 20:41