When a pharmaceutical company spends over $2.6 billion and more than a decade to bring a new drug to market, it needs more than hope to recoup that investment. That’s where patent law comes in. Patents don’t just protect ideas-they protect the entire process of innovation in medicine. Without them, companies wouldn’t risk billions on drugs that might never make it past clinical trials. But patents also set the stage for something just as important: affordable generic medicines that millions rely on.

How Patents Work in Drug Development

A pharmaceutical patent gives a company exclusive rights to make, sell, and distribute a new drug for 20 years from the date it’s filed. But here’s the catch: that 20-year clock starts ticking long before the drug hits shelves. Most drugs take 10 to 12 years just to get through testing, FDA review, and approval. That leaves only about 8 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity. During that time, the company charges high prices to cover R&D costs, fund future research, and make a profit.

For example, when Eli Lilly’s antidepressant Prozac lost its patent in 2001, its U.S. sales dropped by $2.4 billion in a single year. That’s not just a business loss-it’s proof that without patent protection, the financial incentive to develop new drugs disappears. The same thing happened with Lipitor, Advil, and dozens of other blockbuster drugs. Once generics enter, prices plummet. The average generic version costs 80-85% less than the brand-name version. Ibuprofen, once sold as Brufen, now sells for pennies per pill after patents expired in the 1980s.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Bridge Between Innovation and Access

Before 1984, there was a broken system. Brand companies could block generics from even starting development until their patents expired. Generic makers couldn’t test their versions until the patent ran out, which delayed competition by years. That changed with the Hatch-Waxman Act, named after Senators Orrin Hatch and Henry Waxman. This law created a legal pathway for generics to enter the market without waiting for patent expiration.

Here’s how it works: generic manufacturers can file an application with the FDA while the brand patent is still active. They don’t need to run full clinical trials-they just prove their version is bioequivalent to the original. But they must also check the FDA’s Orange Book, a public list of all patents tied to a drug. If they believe a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, they can file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification. That’s a legal challenge.

Once that happens, the brand company has 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is automatically blocked from approving the generic for 30 months. That’s a huge advantage for the innovator. Even if the patent is weak, the delay gives them more time to sell the drug at high prices. But here’s the incentive for generics: the first company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market rights. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s worth hundreds of millions of dollars-enough to justify the legal risk.

Generics Save Billions-But the System Has Loopholes

Today, 91% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They account for just 24% of total drug spending. In 2022 alone, generics saved patients and insurers $373 billion. That’s not a minor detail-it’s a public health win. Without generics, millions of people couldn’t afford insulin, blood pressure meds, or cholesterol drugs.

But the system isn’t perfect. Some brand companies use what’s called “evergreening”-filing new patents on minor changes like a new pill coating, a different dosage schedule, or a new delivery method. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re tweaks designed to extend monopoly control. Humira, a top-selling arthritis drug, had 241 patents filed across 70 patent families. That delayed biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2023, even though biosimilars were available in Europe since 2018.

Another tactic is “product hopping”-switching patients from an older drug to a slightly modified version right before the patent expires. Then they push the new version as “better,” even if it’s not clinically superior. The CREATES Act of 2022 tried to stop this by forcing brand companies to provide samples to generic makers so they can test their products. Before that, some companies refused to share samples, effectively blocking generics from starting development.

Pay-for-Delay: When Generics Get Paid to Stay Away

One of the biggest controversies in patent law is “pay-for-delay” agreements. These are secret deals where a brand company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. The FTC estimates these deals cost U.S. consumers $3.5 billion every year. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these agreements could be illegal under antitrust law-but they’re still happening. In 2023, 12 pay-for-delay deals were still active, delaying generic entry for drugs like Adderall and Singulair.

Why do generics agree? Because litigation is expensive and risky. Even if they win, they might not get to market for years. A guaranteed payout-even if it’s a fraction of what they’d make as the first generic-is often more appealing than a legal battle that could drag on for a decade.

Biologics and the New Frontier

Biologics-drugs made from living cells, like insulin, monoclonal antibodies, and cancer treatments-are more complex than traditional pills. They can’t be copied exactly, so generics for these drugs are called “biosimilars.” The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was meant to create a clear path for biosimilars, similar to Hatch-Waxman. But it didn’t work as planned.

In 2017, a federal court case (Amgen v. Sandoz) threw the process into chaos. The court ruled that biosimilar makers didn’t have to share their manufacturing data with the brand company during the patent negotiation phase. That broke the “patent dance”-a structured, step-by-step process meant to resolve disputes before litigation. Now, companies are stuck in unpredictable legal battles that delay biosimilar entry by years. Humira’s biosimilars only launched in the U.S. in 2023, more than a decade after the drug’s patent expired in Europe.

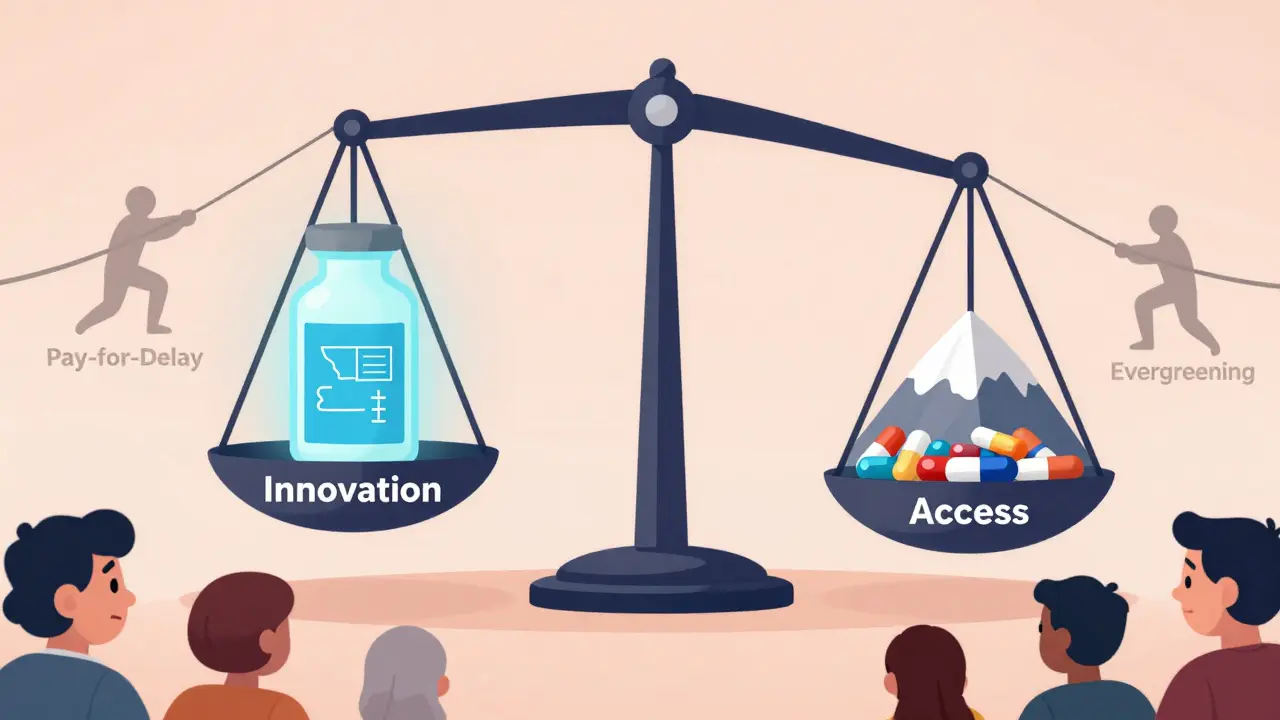

The Balance: Innovation vs. Access

PhRMA, the industry group for brand drugmakers, says strong patents are essential. They point to $83 billion in annual R&D spending and hundreds of new drugs developed each year. Without patent protection, they argue, innovation would collapse.

The Association for Accessible Medicines counters that generics prevented $2.2 trillion in healthcare costs between 2010 and 2020. They say the real problem isn’t too little patent protection-it’s too much manipulation of the system.

The truth is, both sides need each other. Innovation needs protection. Patients need access. The Hatch-Waxman Act got the balance mostly right. But loopholes, legal games, and corporate tactics have tilted the scale. The system still works-97% of generic applications still use the Paragraph IV process. But the delays are growing. In 2005, generics entered the market 2.1 years after patent expiration. By 2020, that jumped to 3.6 years.

What’s next? Congress is debating the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban pay-for-delay deals. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board is also under fire-some say inter partes review (IPR) makes it too easy for generics to knock out patents. Others say it’s the only tool small companies have to fight back.

One thing is clear: patents aren’t just legal documents. They’re economic engines. They determine who gets to make life-saving drugs, at what price, and when. The system isn’t broken. But it’s being stretched thin. And the people who pay the price-patients-are watching.

How long does a pharmaceutical patent last?

A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But because drug development takes 10-12 years on average, most drugs only have 8-12 years of actual market exclusivity before generics can enter.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal framework that allows generic drugmakers to develop and test versions of brand-name drugs before patents expire. It introduced the Paragraph IV certification process and a 30-month stay on FDA approval if a patent is challenged, balancing innovation incentives with faster generic access.

Why do generic drugs cost so much less than brand-name drugs?

Generic manufacturers don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. They only need to prove their drug is bioequivalent to the original. Without the cost of R&D, they can sell the same medicine at 80-85% lower prices.

What is the Orange Book?

The Orange Book is a public list published by the FDA that includes all approved drug products and their associated patents. Generic manufacturers use it to identify which patents they might need to challenge before launching their version.

Can a patent be challenged before it expires?

Yes. Generic companies can file a Paragraph IV certification with the FDA, claiming a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a lawsuit from the brand company and a 30-month delay in generic approval, even if the patent is weak.

What is pay-for-delay?

Pay-for-delay is when a brand drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. These secret deals prevent competition and keep prices high. The FTC estimates they cost consumers $3.5 billion per year.

Do patents protect all types of drugs equally?

No. Traditional small-molecule drugs are easier to copy, so the Hatch-Waxman Act works well for them. Biologics, like insulin or cancer drugs, are complex proteins that can’t be copied exactly. Their generic versions, called biosimilars, face a more complicated regulatory path, and patent disputes are slower and more uncertain.

Adarsh Dubey

Patents are a necessary evil. I get why companies need to recoup costs, but the 20-year clock starting before clinical trials even end feels like a loophole built into the system. India’s generic industry thrives because we don’t play these games-our patients get life-saving meds at 1/10th the price. The system isn’t broken; it’s just rigged for profit, not people.

December 23, 2025 AT 18:15

Georgia Brach

The data presented here is statistically misleading. The $2.6 billion R&D figure is an industry-funded average that includes failed drugs and marketing overhead. Actual incremental development costs for a single successful drug are closer to $500 million. Furthermore, the 80-85% price drop for generics ignores the fact that brand companies still capture 40% of the market post-expiry due to physician loyalty and patient inertia. The narrative is oversimplified.

December 25, 2025 AT 06:39

Joe Jeter

Let’s be real-patents aren’t about innovation anymore. They’re about legal warfare. Companies file patents on toothpaste flavors just to extend monopolies. The fact that Humira had 241 patents is not innovation-it’s corporate greed dressed up as IP protection. And don’t even get me started on pay-for-delay. That’s not business, that’s bribery with a law degree.

December 25, 2025 AT 20:46

Sidra Khan

I read this whole thing and still don’t understand why we let drug companies charge $1,000 for a pill that costs 50 cents to make. 🤡 The system is a joke. Generics save billions, but the big players just keep inventing new ways to delay them. Evergreening? Product hopping? Pay-for-delay? This isn’t capitalism-it’s extortion with a FDA stamp.

December 25, 2025 AT 20:54

Lu Jelonek

As someone who worked in clinical trials for a decade, I’ve seen the human cost of both sides. Without patents, we wouldn’t have the new cancer drugs that are extending lives. But without generics, people skip doses because they can’t afford them. The real tragedy isn’t the patent system-it’s that we treat medicine like a commodity instead of a right. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a compromise. We need to restore its intent, not exploit its gaps.

December 26, 2025 AT 15:51

Ademola Madehin

YOOOOO this is wild. So some rich dude in New Jersey gets to decide if a diabetic in Nigeria gets insulin? And then he gets PAID to make sure it stays expensive?? Bro, this ain’t capitalism, this is feudalism with a corporate logo. I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed. 😭

December 28, 2025 AT 07:14

siddharth tiwari

they say patents protect innovation but i think its all a lie. the government and big pharma are in cahoots. they want you sick so you keep buying. the real cure for cancer? they buried it. look at the orange book-its all fake patents. they dont even test the drugs properly. watch this video: https://youtube.com/xxx

December 29, 2025 AT 11:31

suhani mathur

Wow, so the system that lets you pay $20 for insulin in Canada costs $300 here? And we’re supposed to be impressed by a 30-month delay? Cute. The only thing Hatch-Waxman ‘balanced’ was the scales-on the side of corporate lawyers. Next up: patenting the concept of breathing.

December 30, 2025 AT 14:17

Diana Alime

okay but like… why do we even have patents if the companies just sit on them for 15 years and then sell the rights to a generic maker for $500 million? that’s not innovation, that’s a financial hedge. and the ‘paragraph IV’ thing? that’s just a legal loophole that turns every drug into a courtroom drama. i’m exhausted.

January 1, 2026 AT 13:22

Andrea Di Candia

It’s funny how we talk about patents like they’re this sacred contract between innovation and society. But what if the real innovation isn’t the drug itself-it’s the way we’ve learned to game the system? We’ve turned medicine into a chess match where the board is rigged and the players are all billionaires. Maybe the real question isn’t how to fix the patent system-but whether we should be playing the game at all.

January 3, 2026 AT 03:15

bharath vinay

patents are a scam. they say 91% of prescriptions are generics but that’s because the brand names are so overpriced no one can afford them. and the orange book? that’s just a list of fake patents written by lawyers who never even saw a patient. the whole system is designed to keep you sick and poor. they dont want you healthy. they want you dependent.

January 4, 2026 AT 12:21

Dan Gaytan

Thank you for writing this. It’s rare to see the complexity laid out so clearly. I used to think generics were just cheap knockoffs. Now I see they’re the quiet heroes keeping millions alive. The real villains aren’t the companies trying to innovate-they’re the ones gaming the system to squeeze every last dime. We need reform, not revolution.

January 5, 2026 AT 17:21

Usha Sundar

Patents = monopoly. Generics = freedom. End of story.

January 6, 2026 AT 15:22